China is expanding its economic and political ties with countries across Africa, resulting in a rapid rise in influence here that has sparked concern from the U.S. government.

China is expanding its economic and political ties with countries across Africa, resulting in a rapid rise in influence here that has sparked concern from the U.S. government.

Beijing’s investment and aid to African countries aims to tap both natural resources and a growing middle class. As China burrows into local economies, leaders from South Africa to Ethiopia have been touting its model for development—one that stresses state-led growth, validates tight-fisted political control and offers a powerful counterpoint to the free-market democracy mantra promoted by the U.S.

The embrace of China in Africa’s capitals stands in contrast with complaints also voiced around the continent about Chinese firms’ treatment of workers and concerns over some companies’ environmental records.

In Zimbabwe, even opponents of President Robert Mugabe welcome China’s focus on commerce that doesn’t link aid to politics.

“China’s model is telling us you can be successful without following the Western example,” said deputy prime minister Arthur Mutambara, a member of an opposition party locked in awkward coalition with Mr. Mugabe, who has deep ties with Beijing.

The U.S. is the largest foreign donor to Zimbabwe, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which doesn’t count China as a member. The U.S. funnels much of its assistance through nongovernmental organizations, some of which are critical of Zimbabwe’s government. That hasn’t gone down well with many officials. “China is my favorite country,” said Mr. Mutambara a 45-year-old politician who attended U.S. universities.

Washington has taken notice. Some U.S. officials say the number of governments in Africa finding favor with China’s path of development gives Chinese firms an edge over U.S. competitors and reflects Beijing’s strategic ambitions for the continent.

“It’s quite clear that the model of state-led capitalism is being used as an instrument of China’s soft power,” said Robert D. Hormats, the U.S. State Department’s Under Secretary for Economic Affairs. “It’s part of a broad notion that China’s economic model is successful and can be used elsewhere.”

Mr. Hormats said Chinese investments in Africa came up at a recent meeting known as the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue. U.S. officials have supported Chinese investment and aid to African economies, but they have argued that Beijing should adopt more transparent financing to combat corruption and impose stricter environmental and labor standards to hew to global norms. Such practices could serve China’s interests, U.S. officials say, because big projects wouldn’t be tied to particular governments or officials.

“Our argument is that China can play a constructive role in Africa as investors—but they need to be responsible investors,” said Mr. Hormats.

China says it is simply doing business, largely to support an economy back home, and engaging African governments. Beijing isn’t promoting a particular development model to counter a Western alternative, said Liu Guijin, China’s special representative on African affairs. “What we are doing is sharing our experiences,” he said in a May interview. “Believe me, China doesn’t want to export our ideology, our governance, our model. We don’t regard it as a mature model.”

Many African leaders feel otherwise.

Ethiopia, which has received more than $4 billion in assistance from the U.S. government since 2007, has praised China’s growth and criticized Western “band-aid” approaches to development. Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has lashed out at “extremist neo-liberals” for criticizing his tough stance on dissent, such as jailing journalists and lining the capital with surveillance cameras, which were purchased from a Chinese security company.

South Africa has been sending top officials to Beijing’s Communist Party School to learn how to run state-owned companies more profitably. China is also helping Algeria, Nigeria, Zambia and other African nations build special economic zones to attract foreign investment—similar to the laboratories for industrial reform that spurred its own opening to the world.

Chinese textile makers, real-estate developers and restaurateurs have followed China’s state-owned firms onto the continent. That combination of state-driven capitalism and entrepreneurial zeal has set an alluring example for many African leaders seeking ways to generate investment in their emerging economies.

“The China model is appropriate because Africa needs investment,” says Raman Dhawan, managing director for Tata Africa, an Indian conglomerate with projects dotted around the continent.

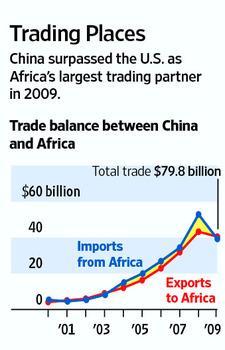

China is now the continent’s largest trading partner, edging out the U.S. Last year, its trade with Africa reached $114 billion, up from $10 billion in 2000 and $1 billion in 1980, according to China’s State Council, or cabinet.

On a continental scale, China’s deal-making pace far exceeds the U.S.’s, according to Mthuli Ncube, Chief Economist at the African Development Bank Group. He estimates Chinese firms accounted for 40% of the corporate contracts signed last year, to 2% for U.S. firms.

Unlike the U.S., which often sends aid money to non-governmental groups, China mostly routes aid through government entities, usually in consultation with leaders about what their priorities are.

In September 2010, China and Ghana signed infrastructure-related loans and other projects valued at about $15 billion, just as the West African nation begins pumping crude from a massive new oil field. In 2009, China signed a $6 billion loan agreement with mineral-rich Congo for infrastructure projects. In Angola, a top supplier of crude to China, Chinese banks have extended about $9 billion in loans and other types of financing, according to a 2010 report from the African Development Bank.

In Addis Ababa, for example, Ethiopia, hundreds of Chinese and Ethiopians have been building the headquarters to the 53 member states of the African Union. China is footing the tab for the $200 million tower and conference center.

While the building is a symbol of tightening ties with Africa, Chinese officials aren’t vying with the U.S. for influence, they say here. “It’s not China versus America. It’s whatever helps the Ethiopians,” says Zeng Huacheng, who has been managing the project as a counselor at the Chinese embassy in Ethiopia. “If we don’t help, Africans will suffer.”

Comments are closed.